This post is part one of two covering the benefits of nature-based activities and camp experiences for youth mental health, and how other practitioners can add nature play into their own work.

Julie Buck’s business is play. Her creative exploration shows up in her affinity for travel, the disc golf course she built in her own backyard, and in the frequency with which you will find her scaling a tree. But beyond her own active life, Julie understands the value of play for children when it comes to physical development, social participation, and processing trauma. This isn’t just any kind of play. Julie weaves time in nature and nature-based activities into her work with children, both in private client interactions and as the Clinical Director of Youth Programming for Aaron’s Place, a Camp Mariposa program from the Eluna Network and Overdose Lifeline that serves youth affected by substance use disorder. Camp and outdoor exploration have been part of Julie’s life since childhood. We sat down to discuss the impact of nature connection on her career and for the children she works with (and how others can incorporate nature play into their work as well).

A lifetime of time outside

Nature has been an important part of Julie’s life from a young age. She grew up spending weekends at a family cabin playing in the woods and creek, which later transitioned into going to camp at age seven until she was a teenager. In college, she returned to camp for a summer job and was director there for a season, staying connected with all her friends who also kept nature as a core component of their lives. Nature connection became harder in her adult years (as it does for many of us), until she moved to Alaska in 2019. Nature took on a more crucial role for her after losing her husband just three weeks into living in a new state. She made the decision not to return to Indiana, where she grew up, and instead chose to explore her new home as she processed her grief. “I felt like I would be grieving him and Alaska if I left because I hadn’t seen it yet,” she shares. Julie describes Alaska as “a whole different animal,” where everyone is outdoors all the time, and it’s easier to be supported to be outside in some way. This time outside was a healing space for Julie to be active and see God’s beauty on display. Her experience in Alaska lent itself to a habit of being more intentional about travel and time outside once she decided to move back to Indiana.

Julie’s personal experience with how nature supported her mental health contributed to the incorporation of nature in her work as an occupational therapist. In 2020, she was able to continue offering occupational therapy sessions to clients by setting up a tent in the middle of a field and providing sessions outside. This change of scenery shifted her private practice and eventually led her to her role with Overdose Lifeline and Aaron’s Place.

For those who aren’t yet familiar with occupational therapy (OT), Julie’s work specifically assists school-aged children with developmental delays, which may include a lack of balance, coordination, fine motor skills or body awareness, or challenges with emotional regulation, transitions, and social participation. All of these things can be addressed in one OT session, she says, giving the example that setting up a tent alone works on executive function, fine motor skills, frustration tolerance, and communication. In Alaska, making bear tambourines to make sure no bears were surprised by outdoor sessions along the trail engaged hand/eye coordination and following directions. Collecting wildflowers for parents as a gift utilizes visual scanning to find the flowers, fine motor skills to pick them, and social participation to think of what colors of flowers someone else might want. Each piece of an activity intentionally contributes to a child’s development, and nature supports the sessions with a calming atmosphere and resources for activities.

Creating a space for learning, laying stepping stones to comfort in nature

Julie’s work has always incorporated elements of nature in some way, although this looks different depending on whether she’s working inside, at a client’s home, or in a natural space. Working with clients outside offers a few benefits that she misses in an indoor setting. For one, there is an element of adaptability that practitioners, kids, and parents all learn from being outside.

“What you can’t get [inside] is coming to a park and realizing it’s a little icy that day, and you had planned to do x, y, or z, but your kid is really enamored by trying to skate across this frozen puddle—and teaching the parent that that is ok, that they’re learning balance, risk management, where their body is in space and how to move it in different ways, all sorts of things! [We learn] that it’s alright, I know we were going to go on this hike or build this project, but we can be flexible and teach kids how to be flexible by being flexible ourselves. That’s just as valuable, if not more valuable, than my planned activity, and it tends to happen a lot more often in an outdoor setting than it would in a contrived environment.”

Julie also notices that when working outside, all parties involved are a little more relaxed. “Just sitting here, we’re in nature and we hear lots of sounds, but they’re all at a level that we can take them in and process them without being bombarded. In our daily life, when you walk into a store there are so many messages being given to you, so many lights and bright colors and sounds, and you are bombarded by it all. Here, there are a million shades of green but it all flows at a frequency our bodies can take in and be calmed by, rather than overwhelmed by. That creates a more conducive environment for learning. In order for us to learn new things, we need to have a space where our brain is ready to receive it. Being outdoors lends itself to learning and a better mental health state. A lot of what I’m doing is trying to rewire the brain and introduce things that have been hard in the past, or are hard in the present, in a space where kids feel safe to move forward and learn about it – so I need an environment that allows for that.”

With all of these positives for outdoor OT and nature play, Julie still comes across children who are new to nature or feel aversion to being outside. To support those clients, Julie focuses on building bridges to meet the child or family where they’re at and letting them lead, one small step at a time, to get to a place where being outside can be beneficial for them. “Incorporating nature for someone who is averse to it might look like just picking a space where we’re indoors but have a view of nature, or playing nature sounds on a recording, or bringing natural materials in for a craft while we’re still inside. Even sitting outside and using chalk on the sidewalk is a way to incorporate nature in a way that is familiar. I think people get overwhelmed, they hear nature and think they have to be this expert, they have to have ‘the 10 things that go in my backpack,’ and know all the first aid – they just get overwhelmed, but it doesn’t HAVE to be that involved. It can be, but it doesn’t have to be.”

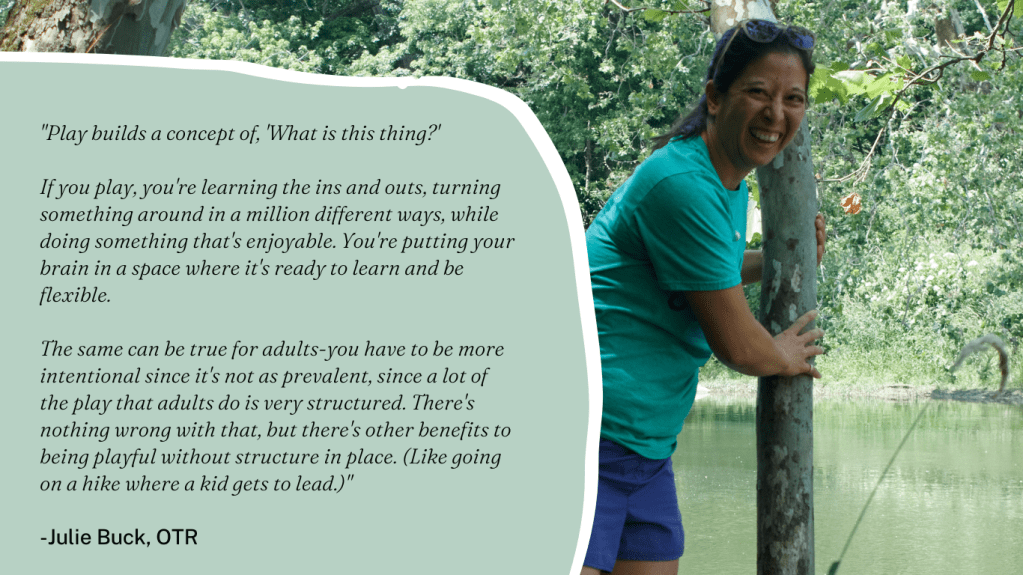

Nature play and allowing kids to have time for creative exploration are some of the great advantages Julie sees to taking her OT work outside. “As an OT, we look at your core occupations. These are activities that are important to you. For kids, play is a major occupation. Play is how we learn…There’s a benefit to play without structure in place.” But youth aren’t the only ones who benefit from nature play! “The same can be true for adults, you have to be more intentional about it since it’s not as prevalent, since a lot of the play adults do is very structured. Children can be great guides on how to play. Like going on a hike where the child gets to lead and they set the pace—if they go off on a tangent making a fairy garden, you get down there and do that with them. It can teach us a lot. It breaks us out of that task-oriented mindset…That’s why I’m always up for climbing a tree.”

Building the nature connection

If your aim is to incorporate more nature activities into your work, whether with children or adults, Julie’s career demonstrates that you can start small and even bring nature indoors to help you get started. (A key point for folks in direct service roles is to make sure your client is in control and leading the way, since not everyone has the same response to different aspects of nature.)

One way Julie suggests getting started is by being open about your intention to have a nature-based practice, even if you’re not “ready” for it. “Telling people that this is something I’d really like opens doors. As doors open, explore if you want to walk through them. Whether that’s a new friendship or a conference to go to, recognize that not every opportunity is going to be right, but the more you talk about your intentions the more opportunities will open up. It’s important to identify your values in doing this work, so you have a framework to reference if opportunities are in line with how you want to incorporate nature or not.”

On top of seeking your own alignment, making sure you’re taking the ethical steps to offer a nature-based practice, whatever that looks like for you, is vital. Julie advises knowing the space you’re going into for outdoor practices, knowing safe places to go or not, and being prepared for what could go wrong. This often includes thinking of client comfort, such as having backup clothing for kids, to make sure everyone has a positive learning experience. “Being willing for kids to say no, and hearing them when they do say no, but also continuing to invite them into nature is key.”

It’s also important to keep the whole family in mind when planning an accessible and inclusive nature experience. “Working in early intervention I wanted to take kids out into nature, I wanted to let them get muddy and dirty, but that means something different when you’re coming from a family where DCS [the Department of Child Services, in Indiana] has been involved before, or you’re worried about putting food on the table or keeping your job and having enough sick days. Many people believe if their child gets wet, they’re going to get sick. Or they don’t have laundry in their home and have to take their clothes to a laundromat, which takes more time and effort and isn’t easy with a child in tow. I had to figure out how to take kids into nature in a way that respects their family and where they’re at, but also gives them some benefits. That may look like me stopping at a park to gather supplies between sessions or using leaves to make a paintbrush instead of using a normal one to adapt to my clientele.”

Finally, Julie recommends being intentional, and being equipped to teach why being outside matters for your context. “Understanding we’re not just playing in the woods, but why we’re playing in the woods, and how balancing on a log is different from balancing on a balance beam in a clinic. There’s a lot of things that can look just like play, but even in an outdoor setting the therapist is being very intentional about bringing all their skills in that setting. Not just saying, we’re in nature, it’s automatically therapeutic, go at it! But applying your knowledge in a nature setting.”

Many of the strategies for incorporating nature-based activities into your work are universal, regardless of profession. Whether you’re an OT, social worker, or community member wanting to apply nature into any other type of work, the key lessons Julie shared can apply. Intentional placemaking and safe, accessible natural spaces are conducive to relaxation and learning. Part of responsible ecotherapy practice includes being familiar with the space you are facilitating activities in so you can steward a comfortable experience for all. It’s also important to provide stepping stones to help the nature averse become more comfortable in outdoor settings, but these strategies for bringing nature indoors or closer to home serve a dual-purpose in making ecotherapy easier to integrate into your work right away. Finally, taking your cue from the person or group you are working with in terms of what’s comfortable and culturally appropriate, along with being able to share why your chosen setting or activities are part of the practice, help maintain a positive outdoor experience for everyone.

What stepping stones do you use to help others feel more comfortable in nature? How do you invite folks in to an outdoor practice or relationship with nature? Share in the comments below!

Leave a comment